The right product in the right place can make box office history

In the fall of 1966, the London-based film producer Albert Broccoli was strolling around the Tokyo Motor Show when a car grabbed his eye.

It was a prototype from Toyota, a sinuous, cat-like coupe called the 2000GT. Broccoli was in Japan to scout locations for his next film, 1967’s You Only Live Twice, the fifth installment in a run of James Bond movies he’d produced. Months later, when it came time to pick the sexy set of wheels that actor Sean Connery would be driving, Broccoli had already made up his mind.

But the producer had a problem.

The 2000GT had only been a concept car. It wasn’t yet in production. And not even the successful 007 franchise was in a financial position to fund the creation of a car from scratch.

Two for the price of publicity

But when Broccoli called Toyota, he made a proposal: Build us a 2000GT to use in the movie, and the publicity you’ll get will more than justify your troubles. Toyota’s brass assented—and built not one car for Broccoli, but two.

The transaction represented more than the usual wheeling and dealing of the movie business: It was product placement at its best.

Fifty-five years later, arrangements just like this one—“embedded marketing” is the new argot—have become an industry unto itself. According to research released earlier this summer by U.K. firm Sortlist, product placement pacts continue to grow at a steady clip. Nothing shocking about that, right?

But the study further shows that brand cameos on film and TV are an evolving business. For example, while today’s hit movies and TV shows do often feature no shortage of brand placements, the productions of yesteryear actually featured more of them. What’s more, while deep-pocketed companies are plenty busy getting their products on set, some of the biggest product placers are smaller brands you might not expect.

More product placements than ever

In the first year of the pandemic, product placements slackened for the simple reason that much TV and movie production was also curtailed. Meanwhile, during the nail-biting summer of 2020, brands were busy turning out ads about empathy and community in lieu of the rather more frivolous-looking chance to appear in a Hollywood flick.

In 2019—that blissful time before anyone had heard of Covid-19—product placements had been rocketing along, having grown for 10 consecutive years. According to data from PQ Media, 2019 saw a 14.5% increase in product placements, reaching a value of $20.6 billion.

The pandemic did put a damper on bringing brands to film and TV viewers’ screens. But the business has since recovered nicely.

According to Sortlist’s head of brand, Aline Strouvens, the confluence of two factors keeps product placements proliferating: the climbing costs of TV and film production, together with brands’ ongoing exodus from traditional advertising channels.

“Product placements have been on the rise as a result of both brands needing increasing exposure and production companies trying to cut down on costs,” she said.

“The film and TV industry faces huge challenges with major streaming services like Netflix taking over and regular TV getting less views. Therefore, a way for film and TV production to still make profits is to increase advertising—and product placement is an easy way to do this.”

On the consumer-product side, Strouvens added, “Brands will pay a lot for product placements, even up to hundreds of millions for big films,” given the ongoing erosion of the power of traditional media.

Even products get typecast

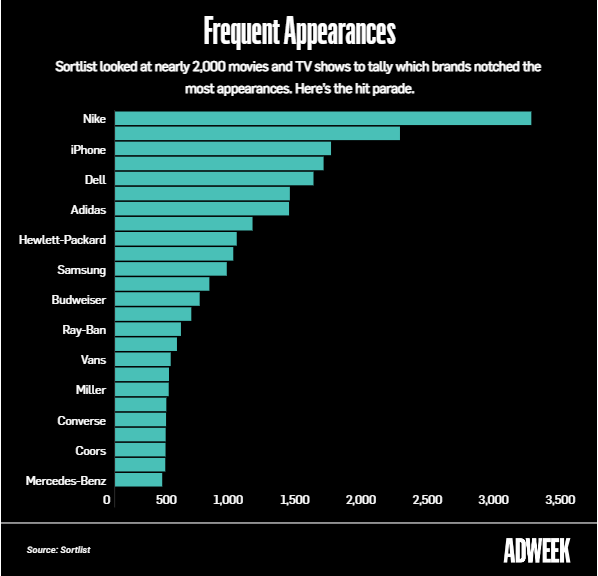

To compile its study, Sortlist looked at 1,954 films. When all the counting was over, 24,635 instances of product placement were tallied. That’s an average of nearly 13 brand cameos per film.

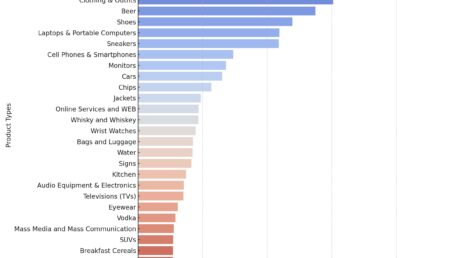

The study doesn’t contain any major plot twists in terms the type of brand best suited for a star turn. For instance, the three most common items to get placed were clothing and non-alcoholic drinks, followed closely by alcoholic drinks. Shoes were a close fourth, followed by food.

Similarly, the most placement-happy brands were generally those with the deepest corporate pockets. The brand that bought the most placements was Nike. Apple was a close second with both its Macbooks and iPhones. Next up were Coca-Cola and Dell, with Adidas and Microsoft also holding places in the top 10.

Best supporting product award: shades and sneakers

Ray-Ban learned the value of product placement once and never had to learn it again. In the late 1970s, sales of the Ray-Ban Wayfarer were so bad that then owner Bausch & Lomb was ready to scrap the model. Then Joel Goodsen (played by a 21-year-old Tom Cruise) donned a pair for a 1983 film called Risky Business. The company sold 360,000 Wayfarers that year. (Not long after, Cruise’s appearance in Top Gun would work similar magic for the Aviator model.)

It’s a similar story for Vans, No. 17 on the list. It, too, learned early on what the right placement can do for marketing.

When it debuted in 1966, Vans were little more than the sneaker of choice for SoCal’s skateboarders—until stoner surfer Jeff Spicoli (played by Sean Penn) appeared in checkerboard slip-ons for 1982’s Fast Times at Ridgemont High, making Vans famous virtually overnight. (For the record, Penn chose the pair on his own, and Vans later supplied as many as the production wanted.)

“Fast Times definitely put us on the map,” Steve Van Doren, son of Vans co-founder Paul Van Doren, told the Los Angeles Times in 2009. “We were about a $20 million company before the movie came out, and we were on track for $40 million to $45 million after that.”

More media, more choices

Another of the study’s notable findings is its list of the movies and TV shows featuring the most brand cameos. Even though product placement continues to grow, the productions with the most brand cameos (at times, too many of them) were often not present-day sensations but rather productions from a generation ago.

For example, while Ocean’s 8 (2018) racked up 76 product appearances, that’s nothing compared to 2001’s Josie and the Pussycats, the colossal flop from 2001 that lost millions despite having no fewer than 109 branded products on screen.

When it came to TV shows, however, product placements have remained more constant. Older series including NBC hit The Office and HBO’s Sex and the City did rack up very high numbers of product placements (1,448 and 806, respectively) while newer shows such as Showtime’s Billions and Netflix’s Stranger Things tended to feature fewer placements (614 and 330, respectively.)

But the blockbuster series of a generation ago also tended to enjoy longer runs. And so Sex and the City’s 806 placements over 94 episodes tallies to 8.6 brand cameos per episode. Stranger Things’ 330 placements over 34 episodes yields 9.7 placements—not a huge difference.

Even so, the fact that the top 10 films ranked by number of product placements contained mostly films from the early 2000s suggests that, thanks to streaming, companies have more choices today than they did just a few years ago. Product placement hasn’t become less popular than it used to be—there are simply more places to place the products.

Trade ya

It’s worth noting that not all product appearances are necessarily bought and paid for. PQ data shows that less than a third of product placements are financial transactions. Most of these agreements (in 2005 figures, as much as 64%) are barters in which “the product serves as the form of compensation,” according to research by Leigh Ann Hornick at the University of West Virginia. Some of the time, of course, a brand simply lands in the script because a writer put it there.

For example, Seinfeld’s “Junior Mint” episode in Season 4 was originally slated to feature M&Ms or Lifesavers. However, both brands demurred once they found out their candies would be accidentally dropped into a patient undergoing surgery. Junior Mints was game—but paid nothing for the exposure.

Similarly, White Castle didn’t pay anything for its considerable spotlight in 2004’s Harold & Kumar Go to White Castle, either. But as recently as 2019, the fast-food chain was still getting mileage out of the film with an Uber Eats promo that gave away 1 million sliders.

As for The Office, it did have an official, long-running commitment with Staples (a major competitor of the show’s Dunder Mifflin office supplier), which is why so many of its products showed up in the episodes. In fact, the partnership was so fruitful that Staples did some product placement of its own, selling reams of Dunder Mifflin branded paper in via its business-to-business arm, Quill.com.

Brands categorically refuse to talk about the terms of their product placement deals. Nevertheless, it’s clear those appearances can take many forms. A brand might pay for a certain amount of screen time. It may want to be featured in a key scene, which typically costs more. BMW reportedly paid $3 million to get its Z3 two-seater into the 1995 James Bond film GoldenEye, for example.

Looking back to 1967, while Toyota only supplied two convertibles—no cash exchanged hands—to land its featured car-chase spot in that year’s James Bond film, the returns did justify the effort. The film went on to gross over $43 million, helping to make Toyota—stateside for just 10 years when the movie debuted—a contender in the American car market.

Originally published by AdWeek, written by Robert Klara