Product placement in movies stretches back to the earliest days of cinema. Wings, the 1927 silent film that won the first Academy Award for Best Picture, prominently featured Hershey’s chocolate bars. Product placement became more commonplace in the 1940s and has only increased since. Today, companies such as Hasbro and Mattel have in-house divisions whose sole purpose is to develop movies whose sole purpose is to sell you their product.

This spring and summer we have entire motion pictures that revolve around sneakers, Barbie dolls, toy robots, and spicy cheese puffs and video games like Tetris and Super Mario Bros. Product placement in movies has been replaced by movies about products. Just because the film is wrapped in pink or stars Ben Affleck doesn’t make it less insidious that PepsiCo—the corporate owner of Cheetos—wants you to forget that you’ve spent upwards of $100 on tickets, concessions, parking, and maybe even a babysitter to see a two-hour commercial for Flamin’ Hot Cheetos. It’s either genius marketing or shameless product pushing, depending upon whom you ask.

So how did we get here?

The golden age of product placement

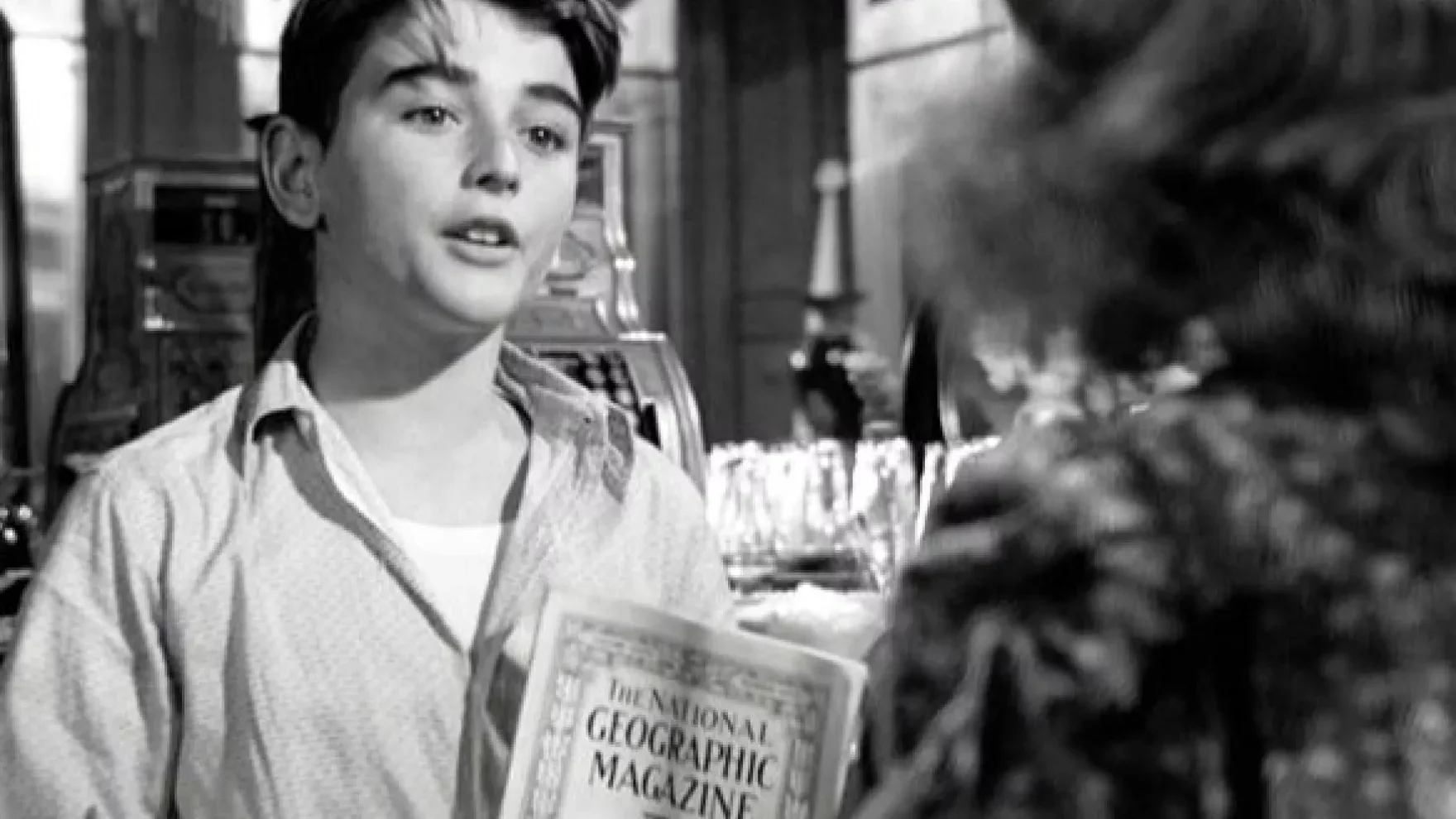

In the 1940s, product placement moved more to the foreground, with characters actually talking about the product instead of it just being featured in the background. You may remember the above scene from It’s A Wonderful Life in which a young George Bailey (Bobbie Anderson) practically points a National Geographic magazine right at the camera and proudly proclaims that he’s been “nominated for membership in the National Geographic Society.”

In the final Marx Brothers film, 1949’s Love Happy, Harpo escapes from diamond thieves on a rooftop using the flying red horse logo from Mobil. By the 1950s and ’60s, product placement in movies was commonplace. The James Bond movies featured luxury brands such as Rolex, Aston Martin, and Dom Pérignon to sell men on the 007 spy lifestyle.

In 1964’s Strait-Jacket, star Joan Crawford insisted that a carton of Pepsi-Cola be prominently featured on the kitchen counter because she was the widow of Pepsi-Cola CEO Alfred Steele and still on the company’s board of directors at the time. Crawford also put in some calls to Billy Wilder during the production of One, Two, Three criticizing the overuse of Coca-Cola in the movie, which prompted the director to toss in some references to Pepsi in the film’s final scene.

E.T. munched on Reese’s Pieces instead of M&M’s, and the world shook

One of the most notorious missed opportunities in the history of product placement occurred when Mars, Inc. turned down an offer for M&M’s to be eaten by E.T. in E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial because the higher-ups felt that E.T. would frighten children. The filmmakers instead approached Hershey Co., which agreed to allow Reese’s Pieces to be featured instead. E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial became one of the biggest box office hits of all time, and Hershey’s profits climbed a whopping 65 percent in the film’s wake. We hope the Mars folks who passed on this partnership were able to successfully transition to whatever their subsequent careers became.

The right product placement in the right movie can translate into huge profits, and filmmakers got the message loud and clear during the Reagan era. Ridley Scott’s 1982 sci-fi masterpiece Blade Runner imagined a 2019 Los Angeles filled with giant digital billboards featuring ads for Pan Am, Atari, and Coca-Cola. Scott reportedly said, “The message being that even in a futuristic dystopian world, Coca-Cola is everlasting.” Scott wanted to convey the idea that corporate power in the near future would be a scary, overwhelming force that loomed over us all. Message received, Mr. Scott.

There are many more examples of product placement in movies after the 1980s, including Converse in I, Robot, Nokia phones in Star Trek, and the 35-plus products featured in Michael Bay’s The Island, which the director reportedly said added “realism.” In 2007’s I Am Legend, Will Smith’s character walks by a billboard for a Batman Vs. Superman movie, which generated enough buzz for Batman V. Superman: Dawn Of Justice to become an actual movie in 2016.

Does it matter if the movie is actually good?

This brings us to the spring and summer of 2023, when products are the actual stars that sell the movie, not the other way around. Whether this is a good or bad thing depends on whom you ask. Movies such as Transformers: Rise Of The Beasts and The Super Mario Bros. Movie are designed to make loads of cash and sell toys and video games. Movies aimed at older audiences have a harder hill to climb but that group’s inclination to reject a feature length commercial can be allayed with good storytelling.

Air may be about how Air Jordan shoes came to be, but Ben Affleck’s biographical sports drama got rave reviews and is about more than just athletic footwear. Eva Longoria’s Flamin’ Hot is a light and clever biographical drama about Richard Montañez, the janitor turned executive who invented the titular Cheetos.

The most interesting test case, though, is Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, which, if the trailers are an accurate indication, has taken some visual and storytelling risks. But even that is a cheat because as much as Barbie dolls are targeted towards young girls, the film seems targeted towards young parents who are open to a more subversive interpretation that, if successful, will engender goodwill and lead to more sales of Barbie dolls.

So is it the end of the world if products are the new stars of movies? Not really … if the film has a compelling story or takes some risks. Luckily, today’s audiences are sophisticated enough to discern between a movie with some style and artistry and one that’s an unapologetic cash grab with no other purpose than to sell toys, games, soda, watches, phones, or some other product. So go ahead and hawk your wares on the big screen. Just have enough integrity that we don’t feel like suckers for allowing you to do it. Now excuse me while I enjoy a Coca-Cola and my umpteenth viewing of Blade Runner.

This piece was originally published by Yahoo and was written by