In the first episode of The Kardashians on Hulu, Kim Kardashian asks the waiter, “Is that from the fountain? Like, the Diet Coke?” gesturing to the soda just brought to the table. “I love a good fountain soda, so.” It’s difficult to determine whether moments like this are a product placement, given there was no indication that the episode was sponsored by Coca-Cola.

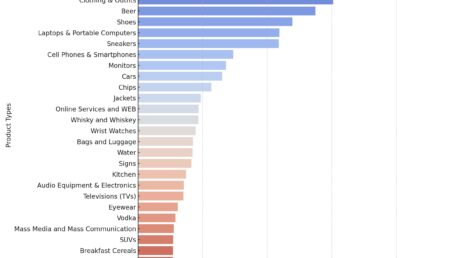

Similarly, there’s no advertising disclosures to be found on Netflix’s Stranger Things, despite there being 140 brands featured in the fourth season’s first seven episodes. Netflix didn’t respond to a request for comment, but previously stated that no brands paid for product placements in season three of the show. And now, viewers may see even more products popping up in shows on streaming platforms—including products that are digitally added after filming.

While identifying select sponsorships as part of a broadcast television show is required by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), U.S. streaming services aren’t yet obligated to disclose product placements in programming. Without significant obligations to disclose product placements in many circumstances, this approach can drive major visibility for brands featured in popular shows, movies, or music videos, especially among today’s advertising-adverse audiences.

At the same time, paid product placements come at a steep price, as this type of advertisement on network and streaming shows range from $150,000 to high seven figures, according to Stacy Jones, CEO of Hollywood Branded, an ad agency specializing in product placements. Plus, advertisers often have limited to no creative control over how a product ends up being featured in a show, despite paying for the screen time. (Sometimes products that are donated to the production can also wind up being part of the story even without a sponsorship, like how a main character on last season’s And Just Like That died while exercising on Peloton’s stationary bike, not an association the brand wanted.)

But some of the barriers for so-called embedded advertising seem to be falling as Amazon and NBCUniversal streaming services recently shared how they’re experimenting with virtual product placements. This next iteration of product placement allows advertisers to dynamically include ads in a show after it’s finished production, opening the doors for more brands to participate.

Some of Amazon’s original shows like Reacher, Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan, and others already feature virtual product placements added after filming. For instance, a bag of M&M’s was digitally added to a bowl on a table in Amazon’s show Bosch, and an M&M’s poster was digitally added to a scene of the hosts of Making the Cut walking down the street.

Meanwhile, Lexus recently partnered with Mirriad to add virtual signage promoting the brand and 3D models of its vehicles in music videos from South Asian-American musicians Mickey Singh and Jonita Gandhi.

“In-content advertising brings many advantages over traditional product placement,” says Stephan Beringer, CEO of Mirriad, a video technology company using AI and computer-vision technology to insert ads in content after it’s produced. Beringer says the virtual ads can be less expensive, reduce the long lead times, and give advertisers more control. “This allows marketers to run their media during their campaign flights—when they’re looking to deliver sales results,” he says. The technology can help entertainment companies earn more revenue from legacy programming.“Something that has the potential to be very interesting and very exciting to advertisers is participating in brand integrations and product placements where you know exactly how the brand is going to be used and how it’s going to look there,” says Jeffrey Greenbaum, an advertising lawyer and managing partner at Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz.

As these advancements change the nature of product placements for brands, the challenge will be in making sure they still appear organically integrated within a program so consumers see them as a seamless plot point.

Originally published by Fast Company, written by Brian Honigman